Information Technology Updates

Some UNI account passphrases expired over the summer of 2020 and were extended temporarily to reduce the challenges related to remote work and learning. These temporarily extended accounts will expire on Wednesday, September 23, 2020 and begin receiving email notifications about their passphrase expiring starting on Tuesday, September 8th, 2020.

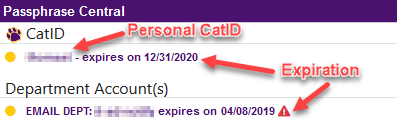

If you have received an expiration email for your CatID or a departmental account, you can change the passphrase yourself by visiting myUNIverse, and choosing the impacted account under “Passphrase Central”.

Note: The expiration date listed in “Passphrase Central” will be incorrect, but these accounts will expire on or before September 23.

How do you tell which account needs to change the passphrase? Look at the username listed in the email notification to determine which account has expired.

If you need assistance changing your passphrase, you can reach out for help through servicehub.uni.edu or by calling the IT Service Desk at 319-273-5555.

You can sign up for the CatID Account Recovery Setup under Passphrase Central and reset your CatID account at any time.

The "Are you available" scam is still alive and kicking. If you receive such a message, even though the display name is a well-known campus name, check the actual email address of the sender. It's likely to be a gmail.com account incorporating the impersonated UNI person into the username portion of the address. Don't be fooled! Mark the message as spam and move on to the next message in your inbox.

If you do interact with the imposter, you'll be asked to buy a large quantity of untraceable gift cards with a promise of reimbursement. That won't happen and you'll be out the money you spent and also filing a police report for the fraud you experienced.

With so many of us now working from home, you are most likely finding yourself remotely connecting with your co-workers using virtual conferencing solutions like Zoom, Slack, or Microsoft Teams. Your family members - perhaps even your children – may also be using these same technologies to connect with friends or for remote learning. Regardless of why you are connecting, here are key steps you can take to make the most of these technologies safely and securely.

Ransomware is a type of malicious software (malware) that is designed to hold your files or computer hostage, demanding payment for you to regain access. Ransomware has become very common because it is so profitable for criminals. More details are available in the OUCH! newsletter on the SANS website, https://www.sans.org/security-awareness-training/resources/ransomware

In the past, building a home network was nothing more than installing a wireless router and several computers. Today, as so many of us are working, connecting, or learning from home, we have to pay more attention to creating a strong cyber secure home. Here are four simple steps to do just that. Read the details in the OUCH! newsletter at sans.org.

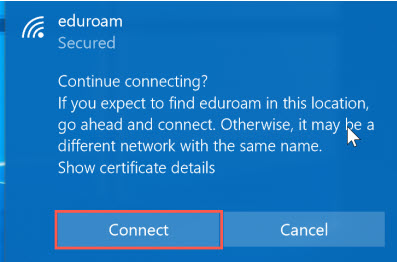

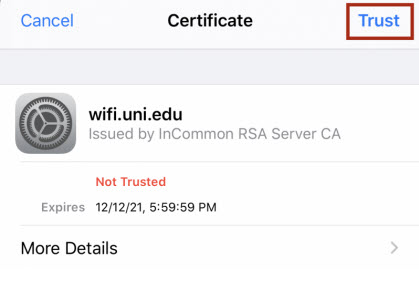

On June 10th Information Technology will replace the security certificate used to secure connections to eduroam WiFi on campus. All UNI-owned and managed devices will be automatically reconfigured for the new connection and nothing will be required. However, personally owned laptops, tablets, and smart phones will potentially be asked to accept a new security certificate the first time they connect to eduroam WiFi after June 10th. These prompts could look something like the screen captures below.

If you have questions or trouble connecting to eduroam WiFi on campus, please visit this IT support article. You can also contact your IT support by submitting a "Get IT Help" request from the Service Hub Portal.

Windows 10

iOS

MacOS

In the past 24 hours, Information Security has been made aware of multiple cases of phishing attempts via shared Google documents. The specific examples I have seen have been sent from a gmail address (itsservice005@gmail.com) and have been named Faculty Evaluation.docx. A familiar UNI personal name is associated with the gmail account, probably changing as the recipients change.

If you receive a shared document offer like this, please use the gmail tools to report the message as phishing and then delete the message. If you find the document within your Google drive, you should:

- Right click on it, choose Report Abuse from the drop-down, and mark it as Phishing on the ensuing page.

While not yet officially confirmed by The Chronicle of Higher Education, there is evidence suggesting a data breach has occurred there. A reasonable step at this time is to login to your Chronicle account and change your password to something unique to that site.

If the password you used on The Chronicle was also used on other sites, you should also change your password on those other sites. It is never a good idea to share passwords between sites. There are password managers that can help you maintain distinct passwords on different sites and also safely store those to enable easy access when needed. Two examples that I use are LastPass and KeePass. They have somewhat different functionality, but are both good options.

Zoom has been getting a lot of attention from the media and the criminal elements of the Internet due to its sudden, massive surge in popularity–10 million users to 200+ million users. There is not a popular application or operating system out there that has not had its share of major incidents. For example, Microsoft releases security patches at least once every month. Most of the time Microsoft is fixing vulnerabilities that can be used to hijack a computer system. Google regularly issues patches for Google Chrome that fix vulnerabilities that could allow a malicious website to execute code on the computer. Sometimes we get multiple patches a week from Google. Likewise, the same happens to Mozilla Firefox.

Hopefully I am not scaring you away from your computer, but I want to make sure our look at Zoom is taken in context. Where were the news articles about Windows, Chrome, and Firefox? They have a much larger user base than Zoom. Yet these security issues have become so routine, they often only get noticed by IT people like myself that are actively watching for security alerts.

Further, many of the articles we are seeing are from Zoom users doing unwise things that are completely out of the control of Zoom. A recent article I saw was about Zoom users uploading recordings of their Zoom meeting online for everyone on the Internet to see. There is nothing Zoom can do to stop people from uploading files to the Internet so that anyone can see them–these same people probably upload all sorts of files with improper permissions. Another article covered a user that disabled passwords on their Zoom meetings to make it easier for their participants to join–it also makes it easy for the bad guys to join. Most of the Zoombombing incidents have been caused by the host or participants accidentally (or in some cases intentionally) sharing the meeting ID and password publicly for anyone to find. Sometimes this happens because they have set their calendars to be publicly accessible. A lot of this reporting is sensationalism just to get clicks and advertising revenue in a time when web news sites are actually under enormous financial pressure. Most advertisers have been cutting back altogether or rejecting advertising on articles that mention keywords related to the pandemic. This has driven the pay per click/view in advertising way, way down.

However, there is also legitimate criticism of Zoom that has been reported.

- Zoom claimed they used AES 256 encryption but in some instances AES 128 would be used. AES 256 is used for Top Secret communications by the government, UNI and most of the Internet actually uses AES 128 for most encryption needs. If Zoom had said they used AES 128 or just simply said AES, it would have been fine. Shortly after discovery, Zoom migrated fully to AES 256.

- Zoom claimed to use end-to-end encryption. The traditional tech meaning of end-to-end has been that communications are encrypted by one user and are not decrypted until they get to the other user, so no points in the middle could see unencrypted data. That technique actually does not work well in a large video meeting where the same information needs to be broadcast to multiple users. So they actually encrypt from the client to the server, decrypt there, then encrypt again when the data is sent back to the other clients in the meeting. The actual video and audio data is encrypted with a shared encryption key used by all users on the same call. This admittedly is a poor implementation of encryption, but it is an efficient way to communicate while still enabling some privacy. WebEx, a competitor to Zoom, does have true end-to-end encryption as an option, but when it is used many features of the software get disabled–so most meetings in WebEx are not end-to-end encrypted either. When pointed out to Zoom, they admitted they were not using the same definition for end-to-end encryption as most tech companies now use. Zoom has announced plans to improve the quality of encryption used in Zoom.

- Zoom's lawyers wrote an overly-broad privacy policy to allow them maximum flexibility so nobody could claim they violated the policy. This is a technique I have seen plenty of other Internet companies use and a reasonable legal strategy. With increased scrutiny, they got called out for it and then changed it.

- Zoom used an off-the-shelf software development kit (SDK) for mobile apps designed by Facebook to allow Zoom users to use Facebook as their authentication credentials. When the SDK was used, it also sent limited analytics data about the mobile device back to Facebook. Such analytics sharing is very, very common in mobile apps and all over the Internet, but it must be disclosed if you dig into the privacy policies and documentation. When discovered, Zoom removed the SDK and integrated Facebook authentication in a different manner.

- Zoom used a workaround on the Mac versions to allow the software to install and run without requiring the user to approve access to the webcam and microphone as Mac OS normally requires now. This was done to make the software easier to use, but legitimate software using such a technique is a major faux pas and opened up the system to other apps being able to gain the same access. This "feature" was removed back in July of 2019.

- Zoom had an issue where malicious links sent via chat could cause a user’s computer username and password to be sent to a remote server if the link was clicked. This is as much a flaw in Windows as it is in Zoom. All Zoom did in that instance was pass a server link sent via its chat feature to Windows for processing and Windows decided in its wisdom to send the username and password for the computer to the remote server listed in the link–but this would only happen if the user clicked the link. This issue has since been patched by Zoom.

Now, all of the above criticisms of Zoom are valid. However, I have seen plenty of other software programs and websites make the exact same or similar mistakes. Here are a couple examples, but this list could be endless.

- Microsoft added intensive analytics and data gathering to Windows 10 and then back-ported the analytics to their older versions of Windows in an automatic update without adequate disclosure to the users.

- The privacy policy for a common grammar and spell check plug-in for web browsers and Microsoft Office allows them unlimited access and permission to all data the user types–even things started to be typed and then deleted before submitting. They claim they do not access this information regularly, but grant themselves the permission to do so in an unlimited fashion and to make commercial use of the data the users provide.

Again, I am not saying that Zoom did no wrong, just that it is entirely typical in how the modern tech community regularly sidelines the privacy and security of users in the name of innovation. We are aware of what Zoom really is doing and view it as no more risky than any other communications and educational platform we regularly use.

As for what you should do to protect yourself when using Zoom, the same advice for Zoom also applies to email, web links, etc. Do not click on links unless you absolutely trust the person that sent it. Likewise, only accept file transfers within Zoom from users you absolutely trust. Whenever possible, do not disable the security features UNI has set as defaults for Zoom. If problems with participants are anticipated, contact the IT Service Desk for advice on configuring Zoom to minimize possible disruptions. Like any other application, Zoom should be updated when security updates come out. Zoom has been quick to patch as issues have been identified.

Likewise, you should keep your operating system, browsers, and other software up-to-date. Many attacks actually use multiple vulnerabilities strung together. Further, you should be vigilant when using the computer. Watch out for things that just do not make sense. Many attacks still require user participation in some fashion–approving an application to run, manually starting an application that was downloaded, allowing a program administrative rights, downloading a suspicious attachment, etc. Be skeptical of anything that seems out of the ordinary. Certainly never trust pop-ups and websites that claim your computer is "infected" or that direct you to call a number to have your computer fixed. Please watch out for phishing attacks, see our website at https://it.uni.edu/phishing for more details about them.

The last thing I will point out is to keep a perspective on other technologies we use all the time and compare their security to that of Zoom. For example, most people do not hesitate to use email, but depending on who you send your email to or how it is routed over the Internet, it is completely possible for it to travel entirely unencrypted over the public Internet. Even if it is encrypted, each mail server along the path will have access to the decrypted contents. Yet we use email all the time for private conversations, online password resets, etc. Social network sites are gathering all types of data from all over the Internet. Google is gathering data from most websites, from its search, from email, and even partnering with credit card companies to link purchases to people to deliver targeted advertising. Many phone conversations, but not all, are routed over the public Internet with minimal security. Yet most of us use these technologies all the time. As such, we should all be more aware of the risks our data and information are subject to all the time, and be vigilant about protecting information we would prefer to be kept private.

I do not have any concerns using Zoom and see it as a perfectly acceptable technology to use in higher education, but I am aware of its limitations. There is always a trade-off between usability and security that must be balanced. In fact, for home users Zoom recently changed that balance towards more secure defaults to protect their novice users. Like any technology, some responsibility lies on the users to properly use the software. That said, I certainly would never use Zoom as the British government did for a cabinet meeting–there the security implications are significant enough to warrant end-to-end encryption with unique login credentials for each user. But admittedly, that would have been much more difficult to set up on short notice.

Let IT-Information Security know if you have any further questions or concerns. We will be happy to address them. We can be reached at security@uni.edu. Also, I will fully admit there is room for debate about when a tech company actually "crosses-the-line." Many of us would draw the line in different spots, so there is room for healthy debate in my assessment.

Eric Lukens, IT-Information Security

Many people prefer to keep their cellphone number private from work relations. Below is some information intended to provide you with the tools to facilitate this privacy.

Does standard call forwarding from my UNI extension reveal my personal number?

- If you are using standard call forwarding from your UNI phone extension to your personal cellphone, your personal number is not revealed to the caller. Typically they aren't even aware their call is forwarded.

- To return a call without sharing your number you can dial *67 to initiate a call that blocks your identity. You can read more about this on Verizon's FAQ. This code can vary depending on your provider, but all major providers use *67.

- It may be helpful let people who you expect to call back know that you will be calling from an anonymous/blocked number.

Does EC500 reveal my personal number?

- If you are using EC500 to send calls to your cellphone, the caller will not see your personal number.

- When you place calls to UNI numbers, your caller id will show as your UNI extension number.

- You can place a call to outside numbers from your UNI number using your cellphone by dialing 319-273-5228. Once you've connected you'll receive a dial tone and can dial out as you would from your desk phone. Read more on Getting Started with EC500.

If you have questions about privacy when interacting with UNI Voice services, feel free to submit a ticket in Service Hub.